For more than twenty years, ever since Cruising World magazine first published an article I wrote, I’ve fancied myself something of a writer. While I only made my entire living from writing for a very short time, it was a rare month that some magazine or other didn’t run a piece of mine while we were cruising. And even once moved ashore, occasional writing opportunities still cropped up from time to time, to keep my hand in with. As the years passed, though, my writing shifted almost entirely to this blog, which doesn’t pay, but has the benefit of complete creative control and the instant publication of anything I care to release on the world.

I had been prepared to not write for money ever again, when the opportunity to sail the Northwest Passage came along. This happened while the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic were still reverberating, and work had never been the same for me after the mandatory shutdowns put swathes of riggers out of business. National Geographic was willing to pay a nominal amount for my presence, and I figured it would be a perfect opportunity to round that out with some writing contracts. Cruising World, barely recognizable after being brutally downsized, then bought and sold and merged and moved several times, was eager for some NWP pieces, and partway into the trip another of my first publishers, Ocean Navigator, reached out to ask for a piece or two for them as well. It felt like my magazine career was getting a second wind.

Nothing moves quickly in the print world, and it wasn’t till we’d been back a few months that the first CW piece ran. I hadn’t even seen the issue yet when I got a phone call: “Hey, you can’t be writing articles about the trip—Nat Geo hasn’t published the story yet, and the documentary’s not out!”

“But you said I could sell some pieces to make up for being paid peanuts!” I protested.

“Yeah, but I didn’t think they’d be this good. You’re gonna get in trouble if you run any more.”

Nettled in spite of the backhanded compliment, I reluctantly called the CW editor and asked him to delay the follow-up article. It eventually ran, but the long wait killed the Ocean Navigator piece. By the time I could give ON the green light, the editor had resigned, the magazine had changed hands, and it wasn’t until two editors down the road that they sent a contract. I had known print media was in decline, but this was barely half of what they’d paid for a short one-page piece twenty years earlier, and barely ten percent of what a feature of its length historically paid. Despairing of anything better in these penurious times, I signed it. Ocean Navigator, on its last gasp then, is defunct now, another casualty of our digital age, and I don’t know if the piece ever printed—even the Wayback Machine can’t find hide nor hair of it.

I was proud of that piece, and really wanted it to see the light of day. So, I’ll publish it here, hoping that the spirit of Ocean Navigator, once among the crown jewels of the sailing periodicals, will not see fit to disapprove from it’s place in the dusty afterlife of canceled magazines.

The Piece in Question:

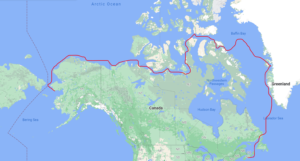

There are certain things in life that no amount of reading up on can prepare you for. Ventures of such breathtaking vastness when compared to any previous experience, that the spirit would quail if it knew what the mind can’t fathom. The biggest of these, for me, was the summer of ‘22 transit of the Northwest Passage, from Maine to Alaska. And not in some custom metal expedition boat, built to dent without breaking on violent contact with ice, but in an 80’s vintage fiberglass cruising boat: a plain old 47-foot center cockpit sloop designed for the Caribbean charter market of forty years ago. It was hardly optimal for any cruising, much less for high latitudes where cold air, cold water, and ice are part of life. It had no insulation, paltry tankage, and instead of a pilothouse, a threadbare canvas enclosure, barely clinging to its frame, limited access to both winches and visibility.

In the weeks after my return, everyone I met would ask, “Well, how was it?” as though a six-thousand-mile voyage from one ocean to another across the frozen top of the world could be described in a sentence or two. Could I say, “It was good?”—yes, it had been good, but it was so much more than that. “Hard?” no doubt, but that doesn’t begin to convey the difficulty. Finally I settled on answering, “It was long.” After all, by the time we wearily tied Polar Sun to a dock in Nome, Alaska, we’d been away for a hundred and twelve days.

But even “long” falls short of description, because that could describe just the final third, as we did a late-season mad dash along the north coast of Alaska, around Point Barrow, and south toward the Bering Sea. And even though the greatest danger—that of pack ice in the ever-darkening nights—was never closer than twenty miles offshore, a windshift to the northwest could have easily fetched it down to close off the inhospitable coast.

We’d seen enough of ice already, on the long voyage that led up to that final push—enough to know that messing around near it in darkness was to be avoided at all costs. For all the months previous, as we sailed north from Maine to Greenland to the Arctic Archipelago, our ice encounters had happened in daylight. The first bergs we saw were at the far end of the Straits of Belle Isle as we approached the Labrador coast, and that coincided with the last real darkness as we sailed toward the Arctic ocean and the land of the midnight sun.

The iceberg charts are relatively simple: they give the number of bergs in each square degree, and if the number is, say, two or four, the chances of meeting one as you pass through that degree are slim. Further up the Labrador coast, there were numbers like twenty-five, which is why it wasn’t a hard choice to just jump off straight across the Labrador Sea for Greenland rather than going any further up that way.

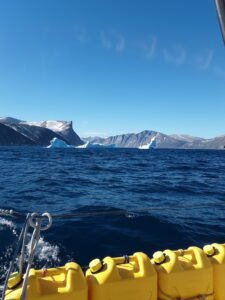

There were surprisingly few as we crossed the Davis Strait toward Nuuk, the capital of Greenland: one as Labrador fell off astern, and one as we neared land on the other side. There weren’t even that many as we wended north along the inner coastal route and crossed the Arctic Circle. As Aasiaat, at the south edge of Disko Bay came near, though, the iceberg frequency increased, and Disko Bay itself was a wonderland of ice.

Polar Sun is a Stevens 47: a tired old cruising boat with an uncored fiberglass hull. There had been some question about whether the Northwest Passage should be attempted without a metal boat. Having built, repaired, and cruised plenty of fiberglass boats, I had no concerns about a solid laminate in ice, but it was hard to ignore the nearly overwhelming tide of skeptics who didn’t share my confidence. In the end it didn’t matter—Polar Sun was the boat we had for the trip, we knew that other glass boats have done the passage, and if we needed to be extra cautious around ice, that wouldn’t be a bad thing at all.

It’s inevitable to shoulder aside small “bergy bits” and brash ice as you wind through the ice barrier on the approach to Ilulissat, situated next to the “Icefjord” from which most of Greenland’s icebergs proceed. In anticipation of that I had made some ice poles for the trip: ten-foot laminated doug fir handles with a spike cut from some leftover bronze plate stock. For over a thousand miles they had lain on deck, stumbled over and snagging things, but now they came into their own as a man on the bow shoved aside the bigger bits of ice that couldn’t be avoided. Even after tying up to the ever-shifting raftup of boats inside the harbor, the poles still got heavy use in pushing stray bergs away from the rudder and windvane shaft.

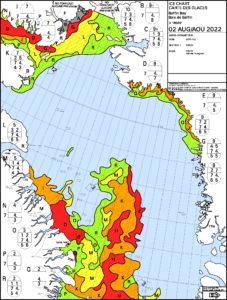

Icebergs, though, are relatively easy to deal with: they usually paint a good radar target as well as being visible from afar, and the debris they slough off can be counted on to drift away to leeward. A far more sinister peril is the pack ice we encountered on the crossing from Ilulissat to Baffin Island. For a few weeks before the crossing we’d been watching not only the daily NASA satellite photos, but the ice charts published by the Canadian Ice Service. The latter express ice coverage and density by means of shapeless colored blobs, with a lettered code to a key giving more details. Even as we left Greenland behind there was still a red blob, signifying 9/10ths coverage, extending as far as 73 ½° North. Skirting the edge of it as close as possible, we had our first look at this new danger that was destined to loom so large in the weeks ahead.

The ice pack appears as a loose jumble of floes, the newer bits cleaner and flatter, the older bits eroded into humps and scoops, with dirty yellow patches here and there. The ice charts code the density in tenths, with anything up to 5/10ths more or less passable by a cruising boat willing to bump into and scrape along some ice, and anything from there to 9/10ths an effective barrier to progress. It’s rare to find a floe by itself—usually where one is, there’s others nearby.

We were surprised to find the ice pack so far north in early August. Historically the “Whaler’s Route,” much further north into Melville Bay, then west into Lancaster Sound, was the only possible way across, but the trend of the last decade or so has been for the ice to clear further south a little earlier, and we had hoped for a fast and ice-free crossing of Baffin Bay. Instead our projected four-day crossing turned into seven when we not only had to go so far north, but a headwind sprang up just as Polar Sun rounded the icepack, and forced us to fall off to the southwest, and fetch the Baffin coast a day’s sail south of Pond Inlet.

There was more pack ice blocking the coast, sparse enough to motor through without resorting to poles, but thankfully dense enough to entirely damp the heavy swell that was running from the north. This virtue of ice is useful to know, since a band of loose ice just a couple hundred yards wide suffices to quell moderate seas. It was startling, though, after being used to seeing icebergs from miles away, how quickly the pack ice can sneak up on a boat. Being very close to the surface, it gives no significant radar return, and not being deep, the forward-looking sonar (FLS) couldn’t detect it. As it was, we were among the first floes, doing eight knots under full sail, while we thought we still had plenty of time to strike sail and get the engine on.

But ice wasn’t the only challenge of cruising higher latitudes. Besides the obvious discomfort of perpetual bone-chilling cold outside and heavy condensation inside soaking everything in contact with the uninsulated hull, there were navigational difficulties. To begin with, things aren’t very thoroughly charted, and a lot potential anchorages and shortcuts inaccessible from lack of soundings. Even with the FLS, approaching a rock-bound coast to anchor was ticklish. Then the compass, sluggish already since crossing the Arctic Circle, becomes useless near the Baffin Coast, and only gradually returns to duty in the Beaufort Sea. Finally, the perpetual daylight, such a wonderful feature of Arctic waters, does preclude any star and planet shots with the sextant, and limits the useful altitude of the sun.

I kept a pretty decent running fix during most of the trip, using sextant shots and bearings, and when the magnetic compass became unreliable, had a chance to practice for the first time with a pelorus. Properly, the pelorus should be permanently mounted on centerline, and is used to take bearings relative to the boat. But there was nowhere safe to mount it on Polar Sun, and I wanted to use it to find True North. This involved reducing a sextant shot of the sun, extracting the azimuth, and sighting the sun with the pelorus set to the azimuth, with a correction for the sun’s travel in the intervening time.

For that moment, then, the pelorus would indicate True North. A lot of effort for a small thing, but useful perhaps if the GPS were to go down in the featureless wasteland we were entering. Having to explain to my shipmates, not only the use of the sextant—which they were all eager to learn—but the use of the pelorus, forced me to think it all through enough times that it made sense to me again.

But did I say a featureless wasteland? While it certainly started out with features—Baffin and Bylot islands are as craggy and mountainous as you could wish—the features diminish once you leave the cliffs of Devon and Beechey islands astern, and for the next several thousand miles the land is little more than gray gravel bars.

It was when leaving Beechey that the ice charts became really important, since either of the two south-leading sounds, Prince Regent and Peel, could be filled up or clear from one day to the next. The daily chart, published in the afternoon and emailed to our Iridium as a compressed file, expresses what the ice was doing when it was drawn. But as our Inuit crewmember Jacob was fond of saying: “Ice always moves.” If there was a gap on the chart, it might have closed by the time you got there. Crossing the Barrow Strait, we found ice where the chart had not shown it, and it was touch and go whether we’d get into Peel Sound as the ice, flowing out of an inexhaustible supply in the Parry Channel, raced us for the entrance.

Further along, a Catch-22 between wind and ice left us trapped in the pack ice for nine days inside of Pasley Bay, and we watched ruefully while the ice cleared all along our route, while the exit remained blocked by 9/10ths ice. When we finally managed to battle out of the bay, proving that a solid fiberglass hull can indeed take quite a lot of ice-ramming, and putting the poles to their ultimate test, it was nearly to get trapped again by a narrow, dense tongue of ice drifting out from the Victoria Strait toward the Boothia Peninsula. We were one of three cruising boats that dodged around that final ice-barrier before it closed up. The next commercial boat, several hours behind, had to call for icebreaker assistance.

That nine days in Pasley Bay, desperately tying up to one floe after another with ice screws as the wind shifted; slipping the anchor cable for later retrieval, playing a losing game with ever-shoaling water in ever-thickening ice, had not only worn us to a frazzle, but made the season late. Even if we pushed nonstop, even if conditions were perfect, it was still two thousand miles through any number of gulfs and sounds and seas, each with few options for bad weather. Several of the crew had to leave, and we were down to two of us aboard for the long, winding, six hundred miles from Cambridge Bay to Tuktoyaktuk, where a relief crew came in to join the boat.

We got around Point Barrow, Alaska’s north-most point, with a lucky east wind in just the nick of time; a week after we rounded it, it was frozen in solid. But the late season still bit hard, and after sheltering in the lee of Point Hope while Typhoon Merbok’s remains wreaked havoc just south of us, we got clobbered not only approaching the Bering Strait, but getting through it in the dead of night with deep-reefed sails, rowdy swells, and the lights of Wales too close abeam for comfort.

If it wasn’t for Nome, that scrappiest of remote frontier gold-rush towns, clinging precariously to the storm-washed underside of the Seward peninsula, we’d have had nowhere to go. The Bering Sea is notorious for bad weather all year, and more so as autumn advances. After being thoroughly scrubbed by the typhoon, there was only one day of calm before a southerly gale piped up to slam the coast again. There probably isn’t a good time to cross the Bering Sea, but there’s definitely worse times, and this would have been one of them. Grateful that we could safely leave the boat in Nome, we flaked the sails, moused out the halyards, and headed home.

“Are you glad you did it?” people ask after I struggle to briefly describe the hardest, longest, coldest, and most dangerous voyage I’ve ever been on. And I can honestly answer that I am glad—the Northwest Passage was worth it, but I don’t ever need to do it again.