Details of Ganymede’s Rig

Synthetic Gaff Rigging with Composite and Alloy Spars

We decided to put a gaff rig on Ganymede for several reasons. The first is that I really like gaff-headed boats: I find in them a beauty and saltiness that can’t be found in triangular Bermudian-rigged ones. Another is that while sailing on Capella I felt a real need for a lower-aspect-ratio rig—I wanted to carry more sail, but lower down where the heeling moment would be less. A third is that Ganymede’s hull, a full-displacement, long keel sort, is eminently suited to such a rig. All the working pilot cutters and quay punts of a hundred years ago whose lines are Ganymede’s heritage were gaff-headed. The rig just suits her look, far more than a tall, multiple-spreader Bermudian would. The last reason, and most compelling, was that I could build a modern gaff rig for less than 1/3 of the cost of a Bermudian. The latter would have required a long and expensive extrusion; my mast was an aluminum light pole (6” OD, 3/16” wall thickness, forty feet long), that cost $700 delivered.

Now some gaffer sailors are also wooden boat purists—they wouldn’t dream of a gaff mast that wasn’t a knotty tree trunk, or a boom not adzed out of a solid spruce tree. But I have no such hang-ups. I wanted all the advantages of a gaff rig, but also the benefits of modern materials—there’s no reason why something that worked really well with old-fashioned materials shouldn’t work even better with lighter, stronger modern construction. I just mentioned the aluminum mast, but my modernization didn’t stop there. The gaff, also, is a piece of aluminum tubing, and the saddle I made out of carbon fiber, epoxy and aluminum bar stock. It took some research to figure out shroud materials. There seemed initally to be a huge array of options in the synthetic rope world, but really there were only two: Vectran, and Dynex Dux, which is pre-stretched and heat-treated Dyneema. Dux was only available from specialty dealers, whereas Vectran could be bought from Port Supply, with an additional full-spool discount. Also, Dux has to be sized large enough to negate the molecular “creep” it suffers under a certain load—it’s less than the creep of plain Dyneema, but still a factor. Vectran, on the other hand, remains static once the constructional stretch has been got out. PBO and carbon fiber weren’t even options due to cost and availability issues, and now that we have synthetics, there’s no excuse to use any kind of metal rope for boat rigging. Though in the dark ages of a decade or so ago it may have been the best option, there’s so many issues involved with fittings, crevice corrosion, weight aloft, chafe, difficulty of splicing and cost, that it’s wonderful that we can now safely move away from all that.

Another reason to choose Vectran was that it can be bought with a polyester cover to keep off the sun, which is a killer to synthetics. Wanting to keep the cost of the rig down, in case it shouldn’t suit after all, I used galvanized turnbuckles from the hardware store that cost $25 each. 7,000 miles later, on the opposite coast, I changed to Colligo Marine aluminum deadeyes, partly because I was convinced the gaff rig was worth keeping, partly because I could afford them at last (the whole boatload cost me about $1200), and partly because the turnbuckles, although US made and of very good quality, were suffering from rust after two years of tropical cruising. Even though I had lubed the threads heavily with Lanocote, the galvanized steel didn’t get along well with the bronze chainplates, and some of them were well-nigh seized. Looking closely at other boats with galvi chainplates and hardware, I’m convinced that steel is an inferior metal for use at sea, especially in the tropics, and every effort should be made to use bronze when possible, aluminum where practical, and stainless steel where the other two won’t do.

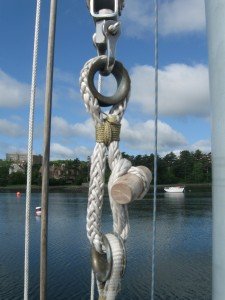

One of the best advantages of synthetic twelve-strand line is that it’s dead easy to splice, so all my shroud ends cost nothing but time and cheap thimbles (or expensive deadeyes, later, which still came in far cheaper than comparable bronze turnbuckles). At the upper end of the lowers and cap shrouds I made leathered soft eyes, which go around the whole mast and eliminate shackles and thimbles. They rest, for a bolster, on a piece of aluminum bar stock which is also the spreader attachment.

How to hank on headsails without chafing the soft shroud was a matter of some concern, and I initially threaded a whole bunch of round brass sailmaker’s thimbles onto forestay and jibstay before splicing eyes into them, thinking to seize toggles onto them for jib hanks. But after learning that headsails could be set “flying”, or independent of the stay, I opted for that instead. One method of setting a stay’sl flying is detailed in Tom Cunliffe’s book “Hand, Reef and Steer”, and while trying to replicate it from memory, I got it all backwards and ended up with my own way. It works splendidly though, especially since the two-part Vectran halyard can be set up bar-tight by leading the fall around the rope drum of the windlass. The flying headsails have two advantages over hank-ons. One is that the stay is not pulled sideways when sailing hard, but is dedicated solely to keeping the mast upright. The other is that there’s not a bunch of stiff and curmudgeonly hanks to have to get in the right sequence and keep lubricated lest they freeze shut and become useless.

Unlike the stay’sl, that hoists by pulling upward on the halyard led through a turning block at the stem, the tack of the jib is sent out to the bowsprit end by a Vectran traveller, then hoisted with a two-part Vectran halyard the conventional way. Having the traveller eliminates the need for ever going out on the bowsprit end, with all the jibnets and railings and platforms that involves, all of which are horribly cluttery on the bows of a boat. To douse the jib we simply turn enough downwind to blanket it with the mainsail, then ease the halyard and gather it onto the deck as it descends. We have done this in all conditions, including a sudden 50-knot nighttime rager, which was the only time the sail dipped into the water as we doused it. It didn’t go far, and pulling it out was no difficulty.

Mast Hoops

One of the most distinctive features of gaffers is the series of hoops that keep the luff of the sail close to the mast. Since they must be made big enough around to easily slide up and down, they can’t be made to hold the sail as close in to the mast as slugs or slides in a track would. It is because of the gaff saddle or jaws, and the hoops, that a gaffer’s mast must be a round straight section: no taper (which rules out using most flagpoles as a mast), and no oval-shaped or box-section (which rules out re-purposing a bermudian mast). Some have suggested that a strong genoa track could be bolted to any stick, and the gaff and sail slides run up that. In theory they could, but the sideways thrust from the gaff, which takes a significant compression load, would put a frightful strain on the gooseneck. It would have to be engineered pretty heavily. This scheme would also allow stays and spreaders to be conveninetly landed anywhere, so with careful planning it could be done, but I would only do it if I didn’t have access to a round section, and a box or oval section was my only choice.

Being that I did have a round, straight section available, mast hoops had to be come up with. You can buy very nice oak ones, riveted with copper, from any sailmaker who has a Challenge Sailcloth account, but wholesale price was $20 each, and I wanted eight, plus a spare. Time to invent. Danielle’s dad does a lot of weed cutting with a heavy-duty string trimmer, and has spools of heavy plastic line lying all over the place. After fidding around with some of that, I bought a spool of my own for about $15, and cutting off a couple fathoms of line wound it into an 8-inch circle. When all the strands were even, I serviced it over with vinyl electrical tape, then serviced over that with 1/8” nylon heading twine. Where the ends of the twine met I used them to lash a little bronze shackle tightly to the hoop. By the time I had eight hoops my fingers were pretty sore (it took a few days), but all of them together had cost what just one oak one would.

Re-rig

When we wintered in Newport News, Virginia, after 7,000 or so sea miles, I took the opportunity to drop the mast and switch from the galvanzed turnbuckles to Colligo deadeyes. It seemed a good time to take stock of the entire rig and replace whatever should need it. Shopping around a little, I got a screaming deal on some 7/16” Validator II line from Samson, which is Vectran with a poly cover. Sure, it was bright blue, and one size bigger than my original rigging, but at 63 cents per foot, too good to pass up. The bigger line fit my new deadeyes better, which had to be sized to fit the 3/8” thick chainplates. So it all worked out. Taking some of the old standing rigging apart for inspection, I found that though the cover had faded in the tropical sun, the Vectran core was still completely intact, none of my splices had slipped, and the minimal chafing was confined to isolated spots on the cover. In short, those shrouds needed no replacement. Still, I like our new shrouds, and being more confident in their suitableness and durability I took the time to decorate the throats of the splices with fancy work—St. Mary’s hitching with turk’s heads aloft and alow. It was a long winter, so I also made a whole new set of mast hoops, taking more care to get them all even and pretty.

On Toggles

While I still had a Port Supply account and a full-time job, I bought a huge pile of Very Expensive Wichard stainless steel wire-gate carabiners. These were to be used for halyard shackles and sheet attachments (not jib, of course; those are tied). I prefer carabiners to the shackles that rely on a split-ring or a tiny knob to pull, and I wanted to be able to quick-release all my halyards and mainsheet, since they serve other purposes from time to time. The carabiners were also to attach the anchor bridle to the bobstay fitting, and lengthen our mooring warps which have rings purpose-spliced into each end. Very useful things, and I’ve retained many in service, but have mostly phased them out of the rig in favor of something better: soft shackles and toggles. While toggles are as old-fashioned as Noah, soft shackles have become far more useful with the invention of 12-strand hollow-braid Dyneema, which makes them as strong as metal ones while being wonderfully inexpensive, especially if you make your own.

There are numerous YouTube videos detailing how to make soft shackles, the hardest part of which is tying the Diamond Knot, which ends up looking like a Matthew Walker’s Knot done in two strands instead of three. I made one or two like that, but much prefer my own version, which is to splice a toggle to one end of a line, then splice a loop in the other end which tightly accomodates the toggle. I find this easier to open and close than an all-rope soft shackle, since there’s something different to see and feel. These shackles also match the other places on the boat that I’ve incorporated toggles, such as the Stay’sl attachment, the jib traveller, the running backstays, and the parrel lines for the storm try’sl.

Right along with toggles, in the simplification department, I should mention bullseye fairleads, sometimes called “Sailmaker’s Thimbles” or “Round Thimbles.” These are very inexpensive round brass thimbles you can splice a line around, and they make great substitutes for blocks in places where the the loaded line is not pulled far, like jib and stay’sl sheet leads. They’re also useful to protect a soft shackle where a block’s metal shackle would chafe it. Recently Antal and Schaefer have been making some larger sizes in aluminum, which I’ve incorporated into Ganymede’s rig in several places. None of these things are modern inventions (in ancient times these “Low Friction Rings” would have been called “Lizards,” and a “Cascading Block System” would have been simply a “Spanish Burton”), but they’re very old, very reliable and simple technology done in lighter, stronger modern materials.

So Ganymede’s rig, though old-fashioned looking from afar, is really quite cutting-edge—alloy and composite spars, synthetic rope rigging, soft shackles—all of which allow me to have a very light-weight, easily handled rig that doesn’t need halyard winches and still spreads 20 square feet of mainsail more than Bermudian-rigged Cape George 31’s do with masts twelve feet taller. Best of all, the entire circus, including all lines, sails and spars, came in at well under $10,000, and there’s nothing I can’t quickly fix or replace with ease using only the tools and parts I have onboard as I cruise.

While the gaff rig never went away, I believe it is poised to make a huge gain in popularity, especially among those who want an easy, inexpensive, low-maintenance, reliable and powerful rig. There’s a world of new materials out there just waiting to be incorporated into the best ideas of the past, and together the results could be amazing.

(Editor’s note, Jan 24, 2021) Now that you’ve read this far, please note than this page is dated: since I wrote it several years ago, Dyneema has evolved in several ways. While DUX is still available, there are several other flavors in the world, and Vectran has been shown to have a shorter lifespan, even when covered, than originally thought. Perhaps I’ll post a discourse on Synthetic rigging soon, now that I’ve worked in the industry for several years, and have an eye on new developments as they arrive.