Sailing season has returned to New England again, and is quickly going into full swing. There’s nothing like the strong blustery winds of May to blow the cobwebs out, shake down everything that’s likely to break, and remind incautious sailors to reef early and keep an eye to weather for sudden gusts. This spring brings an extra note of interest for me, since I’ve been promoted to Captain of the Aquidneck, and now have 37 tons of schoonerific pulchritude under my command for exactly half the days of the summer.

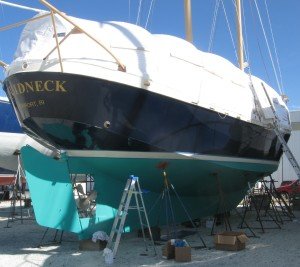

I had expected to end up at the helm of a schooner in Newport eventually—it’s why I went through the extreme expense and bother of securing a captain’s ticket winter-before-last—but I hadn’t figured on getting there so soon. It’s a most welcome circumstance, though, especially with house rent to pay as well as Ganymede to maintain. In fact, knowing since the fall that I’d be a schooner captain come spring had made winter drag extra slowly, and the final thankless, bitter weeks at the boatyard getting the schooner ready to launch nearly unbearable. Still, though the yardwork leaves a black place in the soul that never entirely goes away, eventually the boats go in, the sails go up, and the wheel kicks playfully at a hand that will soon be copper colored with days of endless sun.

Of course there was training; not only for me, but for an all-new crew. In anticipation of this event, I had done a multitude of ins-and-outs from the long, narrow wharf where Aquidneck is berthed, as well as practice swipes at other lanes, nosing in, stopping, and gathering sternway back out again. But still I needed additional coaching, and of the four deckhands only one had ever clapped eyes on a schooner’s deck before. So for the first couple of weeks Curt Porter, the other captain, went out every day, teaching the hands the intricacies of schooner handling while discoursing with me on the proper way to goose the engine in reverse or forward to keep the bows to weather while they fumbled with the sails.

It’s probably good that early season doesn’t bring full boatloads of guests—it’s enough of a challenge for the crew to sail the boat without having four dozen people to trip over. To be fair to them, there’s a lot of halyards and sheets aboard a schooner to manage, as well as topping lifts, docklines and assorted reefing tackle. They’re slowly getting up to speed, and hopefully soon we’ll be able to move from blind routine (After belaying this halyard, cast off this line) to knowing what needs to be done by instinct: looking up at the rig, looking aft for signals from the skipper, seeing something amiss and knowing how to fix it. That’s really the essence of successful sailing on any sort of boat. You must have a perpetual and undistracted situational awareness. In the meantime, Curt and I have to be extra watchful to clap a stopper over nascent bad habits; to gently correct unseamanlike behavior before it becomes routine.

No doubt the new crew will forever have some scars from those early days: not one but two captains perpetually giving orders and coming alongside to tell them they must always pass the springline thusly, and not how they just did it, but when they understand it all they’ll be grateful in the end. For now, they’re just happy that Curt and I work on opposite days, and we’re no longer both there at once to critique their handiwork from separate angles. In fact, we captains won’t see each other again until it’s time to put the boat away in November. Until then, any boat communication will be by notes in the logbook. We could text, I suppose, but who wants to get that involved with work? We usually reserve text messaging to communicate what sort of meat we’re eating on our day off, knowing the other one is stuck with either a lukewarm sandwich or hot dogs from the snack stand on the wharf. Anything from a 5-Guys hamburger and better rates a text: bratwurst on the grill, sirloin tip burritos, pork chops in Jerk Sauce. We share the joy not to rub it in, but to inspire for the next day off.

And so the stage is set: the crew will soon settle into easy competence, the schooner will go and return several hundreds of times, and the captains will exchange many lively text-messages about food. The only pity is that it can’t go on year ‘round, but there’ll be time enough to regret that in the winter. For now, it looks like a pretty good summer shaping up.