Being well-dressed is one of the keys to Arctic survival, and the most important layer is the first. Next to my skin, I wore a full outfit of merino wool. This is better than synthetics because it not only does the same job of wicking away moisture, it gathers body odor far less quickly, and won’t get all slimy feeling after just two weeks. It stays warm when wet, rather than getting clammy. The Smartwool brand is durable, comfortable, and well worth the price. For gloves and sock liners, also merino, I used Sealskins, and though I had a lot of spare pairs, didn’t use them all.

Over the baselayer, from bottom up, I wore wool socks: either commercially available thick merino, or knee socks that my wife knitted. These last were the best, because I could tuck my trouser leg into them, and then just step into my seaboots, which I’ll discuss later. For trousers, we raided thrift stores for all-wool suit pants. Fashion aside, they were far better than any “technical” pants from the outdoor folk, and the wool is not only comfortable, but warm, and it keeps the wind out. Last of all, they were never more than $6 a pair.

The base-layer merino shirt can be worn by itself when it’s warm. Over that I used an all-wool Nordic sweater knitted by my daughter Antigone. Not everyone will have access to her work, but any 100% wool sweater will do. These were my “always on,” clothes; to go outside I had a variety of jackets depending on conditions.

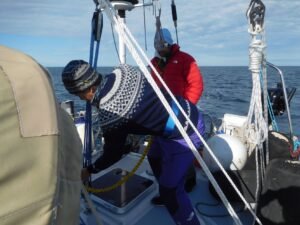

While there’s more “outdoor” companies trying to sell you outerwear than you can shake a stick at, very few of their designers seem to have ever been to sea, and their focus is more on skiing or hiking than seafaring. Certainly you should bring a warm synthetic shell to wear when walking about ashore, but it has little usefulness at sea. When underway in wet and splashy weather, a good pair of foulie bibs is the first consideration. I used Gill’s Explore+ model, and while it was hard to wriggle in and out of, it was the best pair of bibs I’ve ever owned.

The sea boots they make, though dry, did little to keep out the cold, and the super-thin sole wearied the feet after only a short spell at the helm. Instead of using these, I used cold-weather “Muck” brand chore boots: warm, sturdy, comfortable, and durable.

The foulie jacket that matched the boots and bibs was also inadequate: I used it once and put it away for good. Perhaps the high, stiff collar that puts your face in a straitjacket and cuts off visibility is a feature some people enjoy, and maybe, feeling they can still see too much, they put the hood up and become unable to see anything at all. It was impossible, after struggling into the mobility-limiting jacket, to work efficiently at the mast, since to merely look upward required lying nearly flat on your back. Now mind you, I’ve always had a jaundiced outlook against hoods of any sort, so people who enjoy turning their whole body to look in a particular direction might not mind, but I find it useful to turn my head to see things while keeping the rest of my body still.

Having had this prejudice time out of mind, I prepared in advance the foulie jacket I’d been designing in my head for years, mostly on dark and stormy nights at sea when cold water was trickling into the inevitable hole in my bibs. The idea is simple: a long waterproof coat that reaches past your boot tops, and can thus keep the wearer dry even without bibs. Instead of the villainous hood, a high collar, which combined with the time-tested Sou’wester, allows full rubbernecking while keeping the water out, and pockets with drain holes so they don’t become water bags.

The overlapping closure flap is tackable: you overlap it one way or the other depending on the wind so it doesn’t get in. Instead of a zipper, which is hard to manipulate with cold hands, or Velcro, which catches and tears at all your wool underlayers, it’s closed with buttons big enough to engage with glove liners on. Your safety leash can exit through a space between the buttons, meaning you can have it on underneath, and take the jacket off and on without having to take off the harness.

Now at the word “harness” the alert reader will perk up and ask: “Isn’t a harness normally designed to be worn outside of everything, so it has to be struggled into and out of every time a wardrobe change is made?” Well, perhaps with those silly auto-inflating harness vests, but when one is equipped with proper safety gear: namely one of the Knotless Swami belts I invented and brought for testing on the trip, the expensive, impractical, bulky and restrictive PFD/harness/straitjackets can be left on the marine store shelves where they belong. After trying out the Knotless Swami, even the most diehard vest-o-phile on the trip used it exclusively, and not only was safety maximized, but mobility, efficiency, and convenience met together in glorious harmony.

In a concession to the upcoming cold weather, I lined the coat with puffy insulation, and am happy to report that not only did I stay perfectly dry inside the Westport Whaler, as I called it, but it kept me sufficiently warm when worn over baselayer and knit sweater.

As far as gloves, the baselayer was merino gloves from Sealskinz, over these, depending on conditions, I would wear heavy rubber fisherman’s gloves—they come in a variety of thicknesses to suit conditions. The thickest ones are good for wet weather when not much dexterity is required; the thinner ones allow more mobility, but let the cold in faster. For ultimate warmth, I had wool mittens also knit by Antigone. Even if water splashed onto the wool of hands or trousers, they stayed warm. This is the biggest advantage of wool.

Now, some folk are leery of down, but as long as it can be kept dry there’s nothing warmer in the world, and I had a down comforter to sleep under as well as a down coat in case it got really cold. In a well-designed boat with decent insulation, down clothing can easily be kept dry and warm—if the boat won’t stay dry and can’t be warmed, you’re going to be miserable anyway, and might as well sleep under clammy down as wet polyester.

Finally we arrive at the top—literally, where decent headgear is paramount. Here again, the first layer of merino in the form of a hat liner, covered by a knitted wool hat– “the Hatstack,” I call it, was my everyday companion. When rainy, the Sou’Wester of course prevailed, and what I’d like to see is a Sou’Wester with room for a merino hat liner beneath. One day…