One of the reasons that the old saw about necessity being the mother of invention is still around is because it’s pretty much true. In times of need I have often invented, adapted, jury-rigged, and re-purposed whatever was at hand to get the crisis past.

Most of humankind’s greatest achievements have come about for this purpose. Gruk needed a better way to smack Thuk and take his woman, and so the club was invented.

But what about inventions for which there is no need? Somehow, I’ve spent the last several years cooking up things that mankind has already moved past, simply because I have some spare time and an excess of brain cells to misuse. It’s not like I need to kill time; I usually need to be doing something more important when I’m prototyping these other notions.

Of course, I could argue that people actually need these things I’m talking about, and they just don’t know it yet. Take, for an example, Version One of the carrying yoke in the picture.

No one needs such a thing—no one, that is, who hasn’t tried to stagger several miles down a beach with two five-gallon fuel jugs in his hands. After doing this too many times while we were cruising, I tried using an oar across the shoulders, but found that while it helped a little, it put the load too far aft and too much on the neck.

Now, we all remember ancient storybook pictures of milkmaids carrying carboys of milk about with a huge wooden yoke, but what, I thought, if I make one out of carbon fiber, so its weight is insignificant? It took several tries to get the crook right, and several more to get shoulder pads that didn’t dig in and gall. Then I had to invent a harness for the load, and lead it several different ways before it even began to work. But at last I have a prototype worthy of testing, next time I have to carry fuel jugs around.

It will need fine tuning, no doubt, and be interesting to maybe one other person on earth, but there it is.

I ordered, last summer, an industrial sewing machine. After getting by with an antique Pfaff that couldn’t quite get the hiccups tuned out, and wasn’t as powerful as I needed, we just bit the bullet and sprang for a new Consew.

Due to the shipping backups that everyone remembers, it took six months to arrive, but once in position in the insulated shop space I set aside for it, it’s been worth both the money and the wait. Not only am I able to make sails for Pshrimp and the breadboats, I’ve put together some other long-dormant notions as well. The seafaring reader’s eyes will glaze over when I begin talking about rockclimbing, but I’ve been doing that longer than I’ve been sailing, and many of my inventions relate to it, so, with apologies to the uninterested:

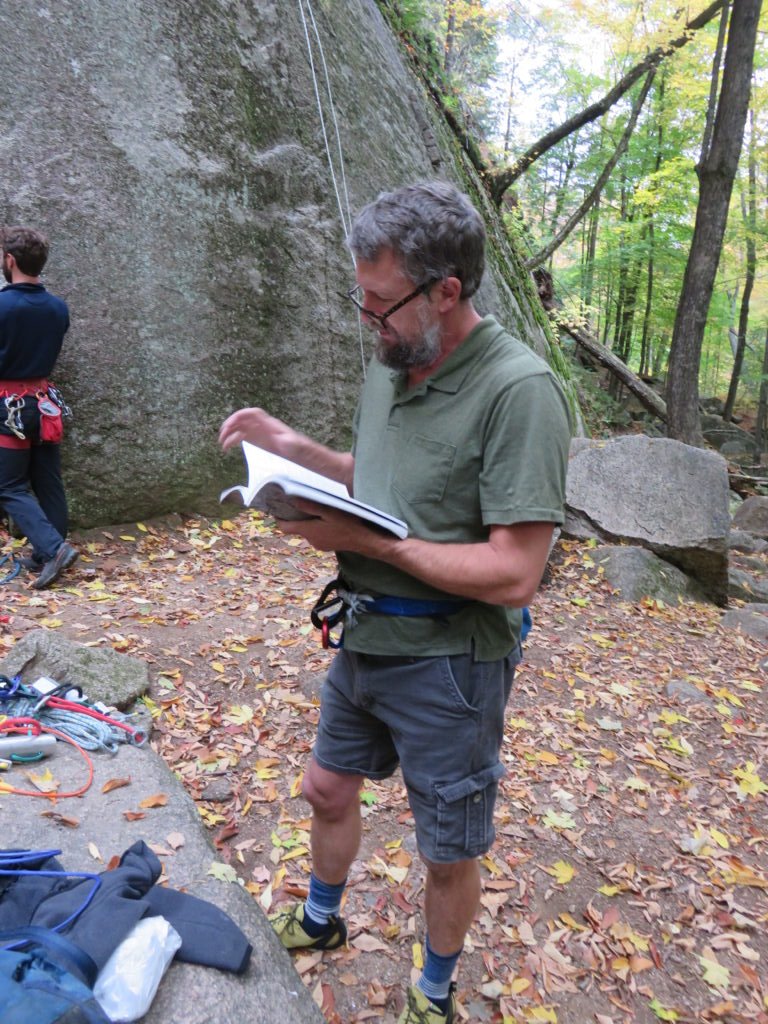

First of all, while most of the world has gone to climbing in harnesses with leg loops, some of us, especially those who’ve done most of their climbing in Yosemite, prefer a simple waist strap known as a “Swami belt.” It’s cheaper, stronger, lighter, gets in the way less, and the only real disadvantage is the way it squeezes your inward parts into jelly when you hang from it for any length of time. It seems like there’d be no way to improve on it, but the one big drawback is that it was always tied with a knot.

You could rotate the knot around to whichever side it wouldn’t be in the way, of course, but still, there it was, with long tails hanging off it. Until now, that is, that I’ve invented the Knotless Swami, secured instead by a dyneema lashing between two sewn eyes.

And with the birth of that ultimate Swami belt technology, we can rise to the next height: the Asymmetrical Side-Lid backpack.

It’s popular for climbing and mountaineering packs to have a drawstring closure with a flap-like lid to cover the opening. This lid often houses small pockets, and in the more diabolical models, there will be a pocket inside as well as out, so you can feel your car keys somewhere in there, but don’t know which pocket to grope in. Nobody likes to take the pack off to root around for peanuts or a water bottle, so you always ask your partner to open up the flap and dig out the guidebook.

Where, reader, does the key, chapstick, wallet, watch, and jackknife-loaded flap-lid go? Straight into the back of your head, and keeps flopping all over your partner’s way while she digs around in the main pocket! Painful for you, frustrating for both, and relations begin to sour before you even reach the climb.

But not anymore, when (if) the side-opening lid goes into production! Your partner will root to her heart’s content in perfect comfort while your neck is blissfully not assaulted by an ill-designed lid.

Another horizon I’ve begun to explore is sustainability: the aluminum carabiners and rope-braking devices used by climbers and arborists tend to get deep grooves worn in them, which forces their early replacement, and in the wet, moldy, mineral-rich worlds of spelunking and sailing, corrosion hastens their end even faster.

My solution has been to begin experimenting with far more durable titanium devices in very simple shapes.

And that brings me back to another necessity: how to invent unnecessary things without the necessary funding. While making practice backpacks out of old sailbags and other salvaged scraps has been relatively cheap (not counting the sewing machine, of course), having Ti machined is shocking expensive. All but one company I’ve invited to help me develop these ideas (and others I’m not free to discuss just now) have not so much as written back. Which leaves me wondering, how do all the dumb, crazy, and needless ideas the world is fraught with get out there? Some inventions are manifestly valuable—the paper clip springs to mind–but what about everything in Skymall magazine? What need spurred those ideas? My suspicion is that invention has another mother, more elusive than necessity, and more capricious in her favorites. I only hope I get to meet her soon.